The Best Castles to Visit in Dublin

Castles hold a powerful attraction on me. They are the most poignant testimonies of our past and capture people’s imagination like no other. Visiting them is always high on my checklist whatever destination I’m travelling to.

With a violent history of foreign conquests and nobles competing with each other for power, Ireland is dotted with hundreds of castles built to ensure protection and control of the land. Others more recently were built as lavish residences for the rich and famous of Irish society.

Dublin city and the surrounding county are no exception. I’ve travelled in and around county Dublin to find the most inspiring of these castles. No doubt in my mind they are also among the best castles to see in Ireland. So here are the best castles to visit in Dublin.

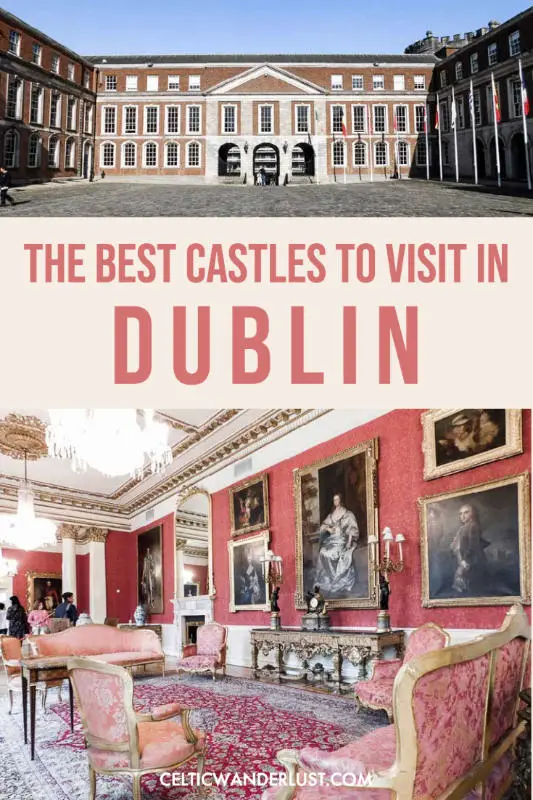

Dublin Castle: Witness the Splendour and Extravagance

Georgian architecture always makes me feel underdressed. The symmetry and proportion of Dublin Castle coupled with an unpretentious exterior seems to impose restraint and a formal dress code. Standing in Dublin Castle’s courtyard, ticket in hand, my baggy shorts feel somewhat inappropriate.

Dublin Castle looks very different now from how it used to. In 1684 a terrible blaze broke out in the Castle. The fire threatened to engulf the Powder Tower and blow up the whole city. The big blast was narrowly avoided but this dark, cold 13th century Norman fortress was (“conveniently” one would say) reduced to ashes. Times had changed and Dublin needed a brand new swanky castle anyway.

Indeed the 18th century was a relatively peaceful time in Ireland, a period called “the long peace”. A small Protestant elite dominated Ireland, most especially Dublin. They were members of the Church of Ireland and rich landowners known as the Protestant ascendancy. They erected magnificent houses and palaces around the city later known as Georgian Dublin.

With little political violence to worry about and a desire for lavish lifestyles, Dublin Castle got a long awaited upgrade. The old fortress transformed into an opulent Georgian residence hosting the Lord Lieutenant’s apartments.

The successive Representatives of the English King in Ireland encouraged the Protestant ascendancy to take part in Viceregal Court life. Dublin Castle became the focus of the social life of the wealthy and powerful, the primary venue of “seen and be seen” events attended by the cream of Anglo Irish society.

The “Social Season” was without contest the highlight of the year in Dublin Castle. The Lord Lieutenant and his wife hosted débutantes balls, banquets and drawing rooms during a six week festive period. It all culminated with St Patrick’s Ball on St Patrick’s Day, March 17th.

Horse-drawn carriages passed through Cork Hill Gate. They took their passengers in their expensive outfits to the castle’s neat Georgian Upper Yard. Inside, a grand wooden red-carpeted staircase led the convives to the ballroom: the impressive St Patrick’s Hall where you can’t help but feel dizzy.

“There is no finer room in Buckingham Palace than St Patrick’s Hall”, wrote Lady Fingall in her memoirs Seventy Years Young. The blue colour is so vivid that it seems to have spread from the carpet to the walls of the Hall. There, golden columns lead the eyes to a vast painted ceiling which depicts the glory of the English King in a grandiose allegorical style. Massive mirrors ingeniously placed opposite the windows reflect both the natural light and the lights of the Waterford chandeliers hanging from an incredibly high ceiling. Banners of the Knights of St Patrick, taking the dust, float on both sides of the Ballroom above our heads. And I can’t feel more out of place in my Summer shorts.

Dancing the waltz or the Quadrille surrounded by this ostentatious decor, the guests competed in their display of wealth: gentry in uniforms and fine silk stockings, corseted ladies in satin and glittering diamond earrings. The richest men of Ireland were here. Among them the Duke of Leinster, who ordered the construction of Leinster House, Dublin’s biggest mansion; Lord Powerscourt, owner of the Powerscourt Estate and 200 km² of land; the powerful Duke of Ormonde, master of the beautiful Kilkenny Castle.

Privileged women as young as sixteen were presented as débutantes to the Lord Lieutenant in the castle’s burgundy-clad, mirror-adorned Drawing Room. Then they could officially join the marriage market that St Patrick’s Hall truly was. Dubbed “The Muslin Martyrs” by George Moore in his novel A Drama in Muslin, they competed for a match, sometimes desperately.

The Countess of Fingall found a match at just 17 during her first Social Season in 1882. She was presented to the 5th Earl Spencer, Princess Diana’s great great granduncle. Constance Gore Booth, daughter of the 5th Baronet of Lissadell, was presented in 1887 at 19 but still attended eight years later…with a chaperone. Constance finally married in her thirties to become Countess Markievicz, a name forever remembered in Irish history when she later swapped the gown for the uniform.

Great splendour is also to be found in the white and golden Throne Room built for the occasional visits of the King or Queen of England. An intricate brass chandelier commemorating the 1801 Act of Union delicately hangs from the high ceiling. The large throne built for the visit of King George IV in 1821 is a homage to his just as large character. He landed drunk in Ireland…

People waited with cringing expectation behind the doors of Fitzwilliam Square and Merrion Square to receive an invitation to the Castle’s balls and dinners, the holy temple of extravagance and social recognition. Meanwhile poverty and diseases killed outside the gate just the same.

Extreme poverty was rife in Dublin. Hungry mobs attacked bakeries during the 1740-41 famine that killed around 450 000 people. The Great Hunger in 1845-1849 didn’t stop the lights from shining as bright as ever in St Patrick’s Hall. 1.5 million people died in those years.

A revolution eventually sounded the knell of the “Social Season”. The music faded away in 1922 with the end of British rule and the abolition of the Lord Lieutenant. St Patrick’s Hall now hosts important State events.

You might also be interested in:

– Visit Dublin’s Most Beautiful Libraries

– 4 Working Distilleries in Dublin for Irish Whiskey Lovers

– 5 Museums To Learn About Dublin’s 1916 Easter Rising

– Dublin’s Best Hidden Gems for Nerdy Travellers

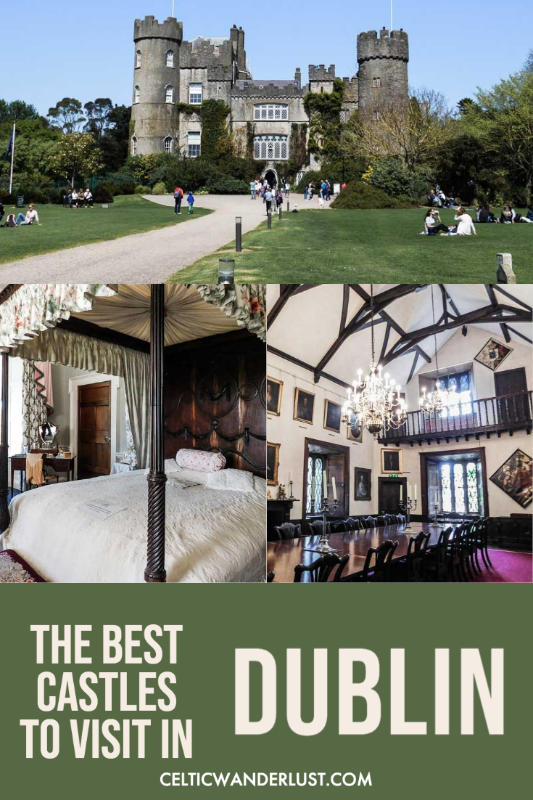

Malahide Castle & Gardens, 800 Years of Prestigious Family History

“Do not touch” says the sign. And yet it is so tempting. With my camera firmly in hands, I get as close as I can to the dark but elegant panelled walls, the finest still existing in Ireland. This is a breathtaking start to my tour in Malahide Castle, a Norman stronghold, home of a prestigious family for 800 years.

The castle was originally a tower house, a fortified medieval residence made of stone protecting a wealthy landowner and his family. You can still see many around the Irish countryside today, sadly often in poor conditions.

Richard Talbot was a knight who arrived in Ireland with the Norman invasion. He was granted the Lordship of Malahide from Henry II in 1184. The family first settled in a typical Norman Motte and Bailey fortification nearby before moving to the site of the present-day castle, possibly around the 14th century.

The Talbots embellished their residence as they rose into prominence. They became the 4th most powerful family in Ireland, symbol of the Anglo Norman dominance over Ireland. They extended the tower house, making space for the most admirable, “touch-with-your-eyes-only”, medieval looking, 16th century Oak Room. The smooth, richly carved panels made of oak depict biblical scenes inspired by Renaissance frescoes in the Vatican. The large latticed 19th century windows overlooking the park injects much needed light into an otherwise dark space.

Each doorway is a step through time. I am now in the glorious Georgian era. The late 18th century small and large Drawing Rooms have everything to keep the viewer enthralled. The crystal chandeliers lead the eyes to high ceilings ornate with magnificent Rococo plasterwork. The orange terracotta colouring of the walls confers a warm feel to the rooms as I gaze at the numerous portraits gazing back at me.

Upstairs the bedrooms give a more intimate picture of the Talbot family. Antique toys remind us that children grew up on this grand demesne. Lord Richard Talbot had sixteen children with Margaret O’Reilly, whom he married in 1765. Where did they all sleep, I don’t know!

Heading back to the first floor, the Great Hall leaves me speechless. Kevin Costner in his Robin Hood outfit must be hiding somewhere! The Great Hall is one of the finest medieval rooms in Ireland. You are immediately drawn to picture a medieval banquet under these centuries-old ceiling beams, minstrels entertaining the guests from the gallery above. Countless intimidating portraits of family members cover the walls. They kept a watchful eye over the European Heads of State dining in the Hall in 1990. Let’s hope the Château Latour didn’t taste too sweet.

On the wall the family’s Coat of Arms hints to how the Talbots, symbol of the Norman invasion of Ireland, survived centuries in hostile lands. “Brave and Faithful” is the family motto represented on the Talbot crest respectively by a lion and a hound. Brave in time of wars and faithful to the English crown.

Sir John Talbot is remembered as “The Terror of the French”. He fought during the Hundred Years’ War and rose to the position of commander of the entire English army. He was finally defeated by dear Joan of Arc (I can’t help but feel patriotic for a second). His lucky cameo in Shakespeare’s Henry VI ensured that his name would never be forgotten.

However, the family’s loyalty to the crown led the Talbots to the edge of extinction at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The enormous painting of the battle dominating the Great Hall is no match for the scale of tragedy that struck the family. England was embroiled in a war of succession between the Catholic James II and his Protestant nephew William of Orange. Catholic and personal friend of James II, made Duke of Tyrconnell and Chief Governor of Ireland, Richard Talbot sided with the Catholic king. Fourteen members of the extended Talbot family took their breakfast in the Great Hall on the morning of the battle, never to return home by its end.

By 1975, another Talbot had departed the castle for the last time, the final member of the family to ever do so. When the property was sold to the state Dublin native, Rose Talbot relocated to Australia, to their Malahide estate ‘down-under’, closing the doors of an 800 year old family history.

Ardgillan Castle, a Life of Leisure in the Irish Countryside

A slightly distressing start. While inquiring about the next available guided tour I find myself kidnapped and taken to a room filled with old muskets and swords. The next tour of Ardgillan Castle isn’t for another hour or so. Why not attend a free talk about old weapons in the meantime! Caught off guard and thinking it might be rude to say no to a free offer, I am dragged to the conference room.

After listening respectfully and looking with sincere interest at antiques for more than 60 minutes, I leave the room appalled but fascinated. I know now that the red wool tassel on the halberd is not for the polearm to look pretty but to suck up the blood running along the pole. A great icebreaker…

I catch up with the tour guide as she shuffles a group of visitors into the first room for a little introduction. Originally from England, the Taylors set up in County Meath where they built Headfort House in the 17th century. They were part of a new landed class called “New English”, a new ruling class that tended to replace the “Old English” aristocratic descendants of the Norman settlers like the Talbots of Malahide. Reverend Robert Taylor, son of Baronet Thomas Taylor, erected in the 18th century a country-styled house in Ardgillan. It was then called “Prospect House”.

The birth certificate of Prospect House still hangs above the fireplace: a huge, white marble slate pompously written in Latin. It reminds visitors that the place was built in 1738 by “Robertus”, I mean Robert, Taylor. Life in Ardgillan must have been as dull as the Reverend. Robert was not the sociable kind. Writing sermons in the solitude of his house was what he did best. He also never married.

Things got more exciting and lively when Robert’s grandnephew, Reverend Edward Taylor and his wife set home in Ardgillan in 1807. Prospect House was embellished and extended with the west and east wings added in the late 1800s. It became “Ardgillan Castle”.

In 1982 the original furniture had been sold before Dublin City Council could buy Ardgillan. Antiques have been donated to breathe life back into the two reception rooms filling up the entire east and west wings.

The impressive size of the Drawing Room, the huge mirrors and the sumptuously carved doors of the dining room are nonetheless evidence of how wealthy the Taylors were. Carved wooden panels run along the bottom part of the walls in the dining room. They project a medieval feel, possibly inspired by Malahide Castle’s Oak Room.

There was life in Ardgillan Castle. The Talbots of Malahide were frequent guests of the Taylors. With other important families they attended balls given at the property. The Taylors were invited to Dublin Castle’s Social Season where they socialised with the rich and powerful Protestant ascendancy.

A hidden door at the back of the dining room leads us to a pantry where wine and other delicatessen are stored. Here dishes are sent up through a lift from the kitchen located downstairs. Ardgillan Castle offers indeed the unique experience to see “backstage” and imagine the life of those often forgotten by history.

A stairway takes the visitor from the pantry down to the large, cold kitchen. Light barely finds its way through the window as the kitchen is located underground. Boys as young as seven or eight worked long hours here, their little hands cleaning countless dishes at the sink.

The visit wouldn’t be complete without a stroll around the demesne. Even more than the Castle’s interior, the breathtaking view on the Irish Sea and the exceptional beauty of the gardens makes a visit to Ardgillan Castle worthwhile.

The exquisite Walled Garden supplied the kitchen with vegetables, fruits and herbs as well providing the Castle with flowers. It is originally a Victorian-style kitchen garden with its perfect lawn and clean lines and symmetry divided by free standing walls. The Ornamental Gardens let the visitor wander through incredible colours and scents. The symmetry and the neat lawn again emphasise the beauty of the flowers arranged around the fountain in the Rose Garden. It’s Pride and Prejudice perfect.

Walking around the meadow surrounding the Castle, I can’t decide on the best view. The palatial alley of yew trees shelters and embellishes the Castle’s south side while the Castle dominates the open view on the Irish Sea on the north side.

The Taylors enjoyed this fantastic view for more than 200 years. As the family fortune dwindled and costs to maintain such a grand domain rose, the property was eventually sold in 1962 to a German industrialist. It was then bought in 1982 by Dublin City Council and open to the public.

Surviving Medieval Ireland in Drimnagh Castle

Neighboured by a school and housing estates, Drimnagh Castle feels very much like a false front of a movie set that has been forgotten by a film production company. Out of place in the midst of a hectic working class Dublin suburb, the little castle has survived the 20th century’s ferocious urbanisation

The area was only sparsely populated in medieval times. Drimnagh Castle was once surrounded by rolling hills and lush forests stretching to the mountains overlooking Dublin. Very picturesque if the enemy wasn’t close by.

The castle was the property of De Berneval, an Anglo-Norman knight who arrived in Ireland with the Norman conquest in the 12th century very much like the Talbots of Malahide. It remained the Barnewall’s (the name later anglicised) property for nearly 400 years.

But the Norman conquest of Ireland was not a smooth stride. The invaders faced resistance from Irish chieftains. In the late 13th century the O’Byrnes of Wicklow launched a raid on Drimnagh Castle that destroyed the wooden structure. A stone castle was then built to replace it. The O’Tooles, a leading Irish family fiercely opposed to Anglo-Norman domination, frequently attacked the castle from their position in the mountains of Wicklow.

The Norman knights had to defend their people from the Irish clans. A moat was dug to enclose the castle, its yard and its gardens; the little river Bluebell supplied the water which flushed into the nearby river Camac. Drimnagh Castle is today the only castle in Ireland which has retained a flooded moat, much to the delight of local ducks.

A drawbridge raised and lowered by hand power allowed access to the gateway. It was replaced by a bridge in the late 18th century. Look further up and you’ll see the “Murder Hole”, another typical defensive feature in Norman castles: a narrow hole used to throw sharp objects, stones and boiling water at unwanted visitors. Contrary to popular belief boiling oil is too expensive to be poured down onto wannabe raiders.

The stairs that lead up inside the late-16th century, 17-metre high tower are narrow, the steps uneven. These are again defensive features to slow down the advance of attackers. The narrow stairway doesn’t allow the intruders to swing their swords with ease while the stairs’ uneven surface makes it difficult to keep their balance.

The basement or “undercroft” is the oldest part of the castle. It was a storage room for food also used as a refuge for people and cattle in case of an attack. Its semi-vaulted ceiling is made of stone to avoid catching fire which could have been disastrous for the entire building.

Within those remparts, the 15th century great hall is astonishing. It is the result of a 10 year restoration project completed in 1996. 200 workers took part in the repair of Drimnagh Castle, including stonemasons, woodcarvers, metal workers, plasterers, tilers and artists.

The floor was re-retiled with tiles taken from St Andrew’s Church in Suffolk Street, Dublin. The roof made of oak was entirely rebuilt using medieval techniques. The funny figures carved at the base of the timbers do not portray any important local medieval figures though. If you take a closer look, you’ll see that one of them wears a watch! They represent those who magnificently restored this grand edifice, leaving their own facetious mark on history.

Outside the restoration work saw the creation of a beautifully maintained 17th century formal garden. No knights or ladies ever walked these perfectly symmetrical alleys but no one will deny that it fits in rather nicely.

Drimnagh Castle has something very picturesque that captures your imagination like no other castle around Dublin. Movie production companies have well grasped its capacity to transport the visitor back in time. Scenes from the BBC series “The Tudors” were shot here and the great hall served as a movie set for Anne Hathaway in “Ella Enchanted”. But the time has come to walk through the gate and rejoin the hum of the modern world, leaving behind a place out of time.

If, like me, you like visiting castles, you know it’s always an exciting experience. Their architecture is breathtaking and they have so many stories to tell. I selected these castles as the most interesting in Dublin so I hope they won’t disappoint you. If Irish history is your jam, consider reading this article about Dublin’s best hidden gems for more historic attractions to visit. Or browse my Dublin travel guide for more inspiration.

Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links. If you click on a link, I earn a little money at no extra cost to you.

RELATED POSTS

Leave a Reply