Guinness’ Goodness to Dublin: Discover the Guinness Legacy

Some days it fills up your nostrils by surprise as you walk down the streets of Dublin. You look up expectantly to see some dark smoke floating above the roofs to indicate its point of origin. But it’s just a smell; the sweet, nutty aroma of barley lingering around the city.

That smell is a silent reminder that Guinness still operates a brewery right here in Dublin city. Founded by Arthur Guinness more than 250 years ago, the Guinness Brewery is a success story like no other. It brought fame, wealth and titles to a family whose name would be forever associated with Dublin.

– Flann O’Brien, Writer

What did Guinness do for Dublin? The Guinnesses not only produced one of the finest beers in the world, but they were well-known philanthropists who helped shape the city of Dublin. Behind some of the city’s major attractions and architectural features lies the fingerprint of this accomplished family. So follow me as I unravel the Guinness connection to some of Dublin’s best and lesser-known sights.

- The Guinness Brewery, Birthplace of the World’s Best Known Irish Beer

- Guinness and the Saving of St Patrick’s Cathedral

- St Stephen’s Green, a Gift from Guinness to the People of Dublin

- St Patrick’s Park and Guinness’s Most Extraordinary Urban Redevelopment

- The Guinness Family: Catching the Glimpse of a Lifestyle

The Guinness Brewery, Birthplace of the World’s Best Known Irish Beer

Remains of railways embedded in old cobbled streets. Brick walls of decades old warehouses towering high around me. Surely I couldn’t be far from the famous Guinness Storehouse? First stop on my Guinness trail: a visit to the old Guinness Brewery was critical to understanding where it all started for the Guinness family.

Turning another corner in this industry-heavy neighbourhood of Dublin, the brick walls appeared taller. Floors after floors of yellow, purple and reddish bricks ruled by symmetry climbing towards the pale blue sky. A massive Guinness sign hanging on the wall in golden letters announced unambiguously that I had finally arrived at the historic Guinness Brewery.

Entering the mouth of this confident building, I was soon wandering in what resembled more a theme park than an old factory. Staff in branded uniforms talking through hands-free microphones welcomed the latest visitors with a well-rehearsed introductory speech while the Guinness Store was already luring them with its enticing merchandise.

I started my self-guided tour staring at a copy of the lease that marked the foundation of the Guinness Brewery. Like a divine relic that demanded protection at all cost, the document bearing Arthur Guinness’s famous signature was enshrined in the ground under a thick layer of glass. Arthur Guinness founded his brewery in 1759 when he purchased a lease on a small brewery at St James’s Gate. Confident in its success, the lease was to be an astonishing 9 000 years long.

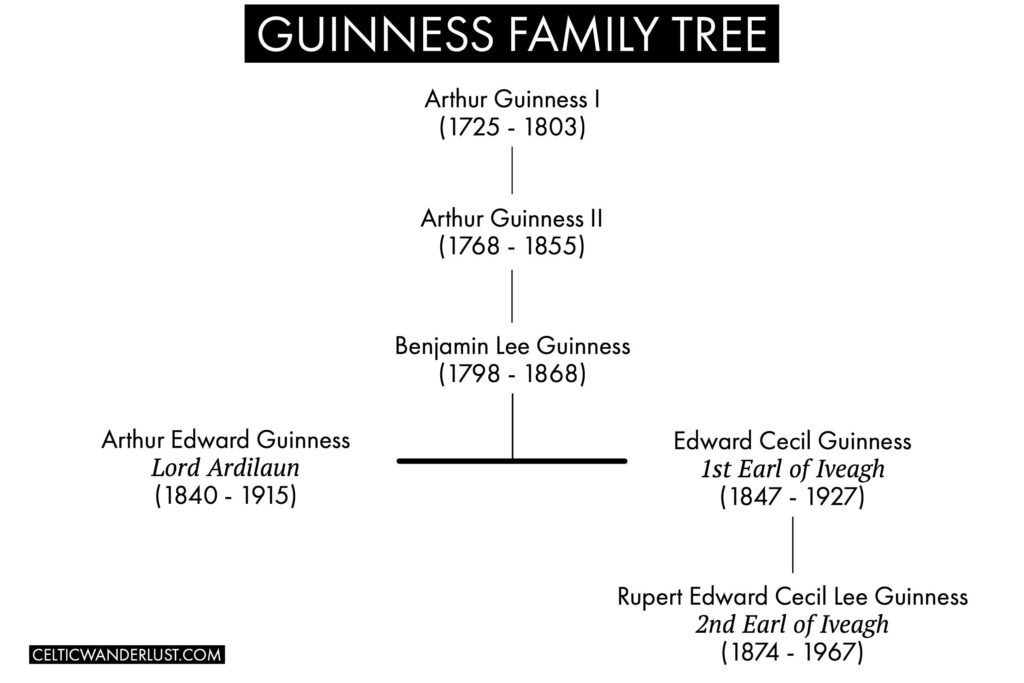

In four generations the Guinnesses turned a family business into Ireland’s most famous success story. At Arthur Guinness’s death in 1803, the business was handed over to his son also named Arthur. Benjamin Lee Guinness took over the brewery at the death of his father, the second Arthur, in 1855. Benjamin Lee Guinness died in 1868 and the family business was bequeathed to his two sons, Arthur Edward and Edward Cecil. Edward Cecil assumed sole proprietorship of the company when Arthur Edward sold his share to his brother in 1874.

From the ground floor to the Gravity Bar resting like a flying saucer on top of the Guinness Storehouse, the story of the brand was told in a strange mix of entertainment (was the DJ over the top?) and educational material. Floor after floor, room after room, I uncovered the ingredients and brewing that made the beer so unique, the skills required to build a cask from scratch and the history of Guinness’s genius advertising.

But Guinness wasn’t only about creating a successful beer. With 40% of the population of 19th-century Dublin living below the poverty line in a city with the highest rate of contagious diseases in Europe, working for the Guinness Brewery was a godsend. The Brewery was a hive of activity providing work for more than 5 000 people at its height in the 1950’s.

Renowned philanthropists and deeply religious, the Guinnesses were generous with their employees. At a time where the state social welfare was non-existent, workers at the Brewery received sick pay and – a thing unheard of before – paid holidays, while widows were entitled to a pension. Medical officers were hired to staff a Dispensary looking after the workers but also their families, all together a community of around 20 000 people in the 1950’s.

The taste of the famous black drink was finally revealed as I enjoyed a complimentary beer in the Gravity Bar, my eyes on Dublin’s autumnal skyline. The 360 degree view over the city was certainly adding to the experience. Down below, the old railway system had long been retired. Instead shiny trucks were now taking the dark stout from Guinness’s newest facilities to the four corners of the world.

You might also be interested in:

– 4 Working Distilleries in Dublin for Irish Whiskey Lovers

– Phoenix Park, Dublin | A Guide to Its Historical Treasures

– 15 Sights in One Day | A Self-Guided Walking Tour of Dublin

– 5 Fascinating Museums To Learn About Dublin’s 1916 Easter Rising

Guinness and the Saving of St Patrick’s Cathedral

St Patrick’s Cathedral owes most of its fame to Jonathan Swift, best known as the author of Gulliver’s Travel who was buried in the floor of the grand building. Swift was also Dean of the Cathedral from 1713 to 1745. Like many visitors, some possibly on a Dublin literary walking tour, I searched for his epitaph, written by the world renowned author himself (in Latin!), on the wall of the Cathedral.

But the imposing edifice built in the 13th century by the Anglo-Normans would be a ruin today if it had not been for the extreme generosity of someone slightly more obscure. Standing outside the Cathedral near the south door, out of reach behind a tall iron-cast fence and ignored by most, was the statue of its benefactor: Benjamin Lee Guinness.

In the early 19th century St Patrick’s Cathedral was in poor conditions to the point where people feared it might collapse. The building was in dire need of renovation. A costly renovation. So costly that its reconstruction from scratch was thought to be cheaper.

Benjamin Lee Guinness, grandson of Arthur Guinness and the richest man in Ireland, proposed then to finance, on his own money, the restoration of St Patrick’s Cathedral. The catch: he requested no interference from the Cathedral board while the work was ongoing. £150 000 (an absolute fortune!) was to be spent on the renovation from 1860 to 1865.

Benjamin Lee Guinness oversaw the work himself and performed a series of changes based on his own liturgical taste. As I walked down the nave, the most important of these changes became obvious. The screens which separated the nave, choir and transepts had been removed, creating a large open plan space inside the cathedral. Approaching the centre of the building, the colourful banners of the Knights of St Patrick which hung above the choir stalls seemed to be floating in the air, filling up the huge space left open.

Benjamin Lee Guinness was made a Baronet in recognition of his service and generosity. His sons Arthur and Edward continued to support St Patrick’s after their father’s death. The magnificent eye-catching yellow, red and blue tiles throughout the Cathedral were paid for by Arthur. They were inspired by surviving medieval tiles found in the baptistry. Edward would later donate a new set of bells.

Benjamin Lee Guinness saved one of Dublin’s most beloved landmarks that attracts thousands of visitors each year. But the conservation work has been ongoing ever since. In 2013 the Lady Chapel dating from the 13th century and later used by French Huguenots was restored to its former glory. Among marble statues, commemorative monuments and the tombs of Irish presidents, the Cathedral houses over 200 monuments under its roof.

St Stephen’s Green, a Gift from Guinness to the People of Dublin

I have walked through St Stephen’s Green so many times now that I sometimes forget to notice the beauty of Dublin’s most visited Georgian garden square. One afternoon in October as the leaves were turning red and pilling up on the soft ground, I stopped and looked up. Here he was, another member of the Guinness family to whom Dubliners owed so much.

Sir Arthur Edward Guinness, great grandson of the first Arthur, also known as Lord Ardilaun, was striking a pose on the edge of St Stephen’s Green, facing the Royal College of Surgeons. Like his father Benjamin before him, he had his own seated statue.

Arthur Edward Guinness had inherited the brewery together with his younger brother Edward Cecil. But he later sold his share in the business to his sibling to pursue his real interests: public life and philanthropy.

He completed the renovation of the Marsh’s Library located beside St Patrick’s Cathedral. But Arthur Edward Guinness would be best remembered for giving St Stephen’s Green to the people of Dublin.

What had been a piece of land on the edge of Dublin used for grazing became a private park for the local and wealthy residents following the construction of a wall all around it in 1664. At the initiative of Arthur Edward Guinness, the Parliament passed an act in 1877 to reopen the Green to the public. A. E. Guinness offered to pay for the redesign of the Green which reopened in 1880. Since then, the layout has stayed much the same.

October was unusually warm this year and Dubliners were enjoying their lunch on the benches and grass of St Stephen’s Green. A tourist shouted in her American accent her incredulity at the flowers’ bright colours laid in front of her, wondering if they had been dyed. The pond attracted young children eager to feed the sociable ducks and cranky swans while parents were taking on the task of keeping the greedy seagulls at bay.

All around the Green, elegant Georgian buildings had remained. One was host to a secretive Gentlemen’s Club almost vanishing under a thick wall of ivy. Another was home to a private school for upper-class kids in smart grey uniforms. Echos of cheerful voices could be heard from outside the popular Little Museum of Dublin, a Georgian house filled with antiques and vintage posters donated by the public and staffed with the most enthusiastic tour guides in the city.

Since its reopening in 1880 St Stephen’s Green has become one of Dublin’s most important features, a recurring character in Dubliners’ social life. In St Stephen’s Green, office workers bask in the sun during lunch time, teenagers sit on the edge of the fountain comparing their latest purchase from their shopping spree in nearby Grafton Street, language exchange students buzzing with excitement regroup as bees under the leafy canopy. If you’re lucky enough you might even catch a small orchestra playing under the roof of the old bandstand.

St Patrick’s Park and Guinness’s Most Extraordinary Urban Redevelopment

My curiosity aroused by odd looking buildings found between Dublin’s two cathedrals, I found myself investigating the neighbourhood. I was scrutinising the old brick facades for a clue when I read “Iveagh Trust” engraved in beautiful calligraphic letters. Retreating to a bench in nearby St Patrick’s Park, I googled the discovery on my phone.

Iveagh was another name for Edward Cecil Guinness, brother of Lord Ardilaun. At the end of the 19th century, Edward was in command of the Guinness Brewery and turned it into the largest brewery in the world. He became the richest man in Ireland after floating the company on the London Stock Exchange in 1886. In 1891, Edward was made Baron Iveagh and Earl of Iveagh in 1919.

His father saved St Patrick’s Cathedral from the brink of collapse. But in the late 19th century, the Cathedral’s bell tower overlooked filthy tenements and dirty alleys that were developed without proper planning. With more than 40% of the population under the poverty line, the living conditions of Dublin’s working class were dreadful.

At the initiative of the Guinness family a huge program of clearance was undertaken. By Act of Parliament, the area near St Patrick’s Cathedral was acquired by Edward Cecil Guinness. In 1901, 20 years after his brother gave St Stephen’s Green to the people of Dublin, Lord Iveagh gave Dubliners a new park to enjoy: St Patrick’s Park.

Here I was sitting in a century-old park created yet again by a member of the Guinness family, sheltered for a moment from the hustle-and-bustle of the city. I watched the weeping hollow bent over the neatly cut grass, listened to the clattering of the fountain as the water dropped in the circular bassin. St Patrick’s Park gave the Cathedral a picturesque setting where visitors could sit down and admire quietly the architectural achievement standing in front of them.

The clearance didn’t stop there though. Edward Cecil Guinness, founder of the philanthropic trust called the Iveagh Trust, made it his mission to provide affordable housing and amenities to Dublin’s poor working class.

As I investigated further the area north of St Patrick’s Park, the name “Iveagh” kept popping up on facades. Bride Road was flanked by buildings bearing the names “Iveagh Baths” and “Iveagh House”. The “Iveagh Trust” name showed up again on the impressive exterior of the building fronting St Patrick’s Park on its north side.

The area between the two cathedrals had seen the most impressive urban redevelopment undertaken by Lord Iveagh and his Trust. Between 1899 and 1915, the area was dramatically transformed. The Trust oversaw the construction of 5-storey residential blocks housing 244 low income families, a massive hostel for single men, mainly rural migrants seeking work in Dublin, a swimming pool and a large recreational hall with classrooms.

Fresh laundry hanging from narrow windows was evidence of the continuing residential function of Dublin’s first modern apartment blocks. Today the Iveagh Trust continues the work started by Edward Cecil Guinness a hundred years ago and still provides affordable housing to the people of Dublin.

The Guinness Family: Catching the Glimpse of a Lifestyle

“Where are the descendants of the Guinness family now?” I asked myself. Well, mainly in the UK. After the death of Edward Cecil Guinness, his son Rupert Edward Cecil Lee Guinness became chairman of the Guinness Brewery until his death in 1967. His family home was in Surrey, England.

I was still hoping to catch a glimpse of the wealth and opulence of the Guinness family when they still lived full time in Dublin. My first clue came once again from the name “Iveagh”.

Guinness’s Sumptuous Family Home and the Iveagh Gardens

South of St Stephen’s Green at number 80 stood a building with the most stately appearance. Flanked by red brick Georgian houses, the neoclassical building with its pillars and white facade couldn’t be missed. The gold plaque by the door indicated “Department of Foreign Affairs”. The building was also known as the “Iveagh House”.

Bought in 1862 by Benjamin Lee Guinness, what was now a ministerial department used to be Guinness’s family home. The building was donated to the Irish State in 1939 by Rupert Guinness. A working building, the headquarters of the Department of Foreign Affairs opens its door to the public only once a year during National Heritage Week. Its sumptuous interiors would have to wait.

The house had large gardens. Donated by Rupert Guinness, the gardens were turned into a public park known as the “Iveagh Gardens”. Enclosed by walls and entirely surrounded by buildings, the entrance wasn’t the most obvious to find. I stumbled upon the main gate off Harcourt Street.

I suddenly felt a strange relief. As I passed the first trees, the noise of the city quickly faded away and all I could hear was my steps on the gravel. I found people asleep on the grass around the archery ground as if the gardens had put them under a dreamy spell.

Afraid to disrupt the agreed-upon silence, book reading, sunbathing and whispering were everyone’s favourite activities. Hidden behind walls of thorn and flowers, those looking to meditate favoured the more intimate setting of the rosary. At the far end of an alley, the refreshing sound of a cascade surrounded by exotic ferns made sure I forgot for a time I was right in the middle of Dublin city.

Farmleigh House, Guinness’s Rustic Retreat

Not having the opportunity to visit the Iveagh House, I focused my attention on another house that the Guinness family used to own in Dublin. Hidden away in one of Phoenix Park’s many corners, Farmleigh House was an Edwardian mansion bought by Edward Cecil Guinness in 1873 as a “rustic retreat”. The house remained a property of the Guinness family until it was sold to the Irish State in 1999.

Farmleigh House now serves as the official Irish State guesthouse for dignitaries on a State visit to the Republic. As the tour guide opened the main door for a small group of curious visitors, I was secretly hoping to bump into a celebrity. In vain. The house was empty that day.

Passing through the landing, instinctively we all looked up, our attention drawn by the lavish chandelier and high ceilings. We moved through the dining room where antique Italian tapestries had been placed against the walls, one shamelessly cut short to fit above the fireplace.

The Billiard Room was certainly the most striking room of all with its walls covered in blood-red cotton fabric. Here the men would smoke cigars away from the Ladies. A trap in the wall had even been designed to evacuate the smoke when private discussions and billiard games had gone for too long.

In the west wing was the chandelier-clad ballroom where the wooden walls had been skilfully painted to look like marble while its floor wore the signs of thousands of stabbing high heels. We finally left the house through the warmth of the spacious conservatory, hanging out for a moment with the house’s only permanent residents: the tropical plants.

Many come to Dublin for Guinness the beer. Who could blame them. Guinness is the most successful product Ireland has ever produced and has no doubt contributed to putting Dublin on the map.

Guinness is not just a beer though.

Self-made entrepreneurs, the Guinnesses left their mark on the Irish capital like no other family, spending vast amounts of their wealth to better the life of ordinary Dubliners. As I walk around the city streets and the aroma of barley catches my nose once again, I don’t look up for the invisible smoke anymore. I look around, knowing Guinness is everywhere in Dublin.

Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links. If you click on a link, I earn a little money at no extra cost to you.

RELATED POSTS

Leave a Reply