Huguenots in Dublin | Discover the City’s Forgotten French Heritage

Huguenot was the name given in the 16th century to French Protestants born from the Reformation. With France engulfed in religious and political strife pitting Catholics against Protestants, culminating in 1572 with the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, some Huguenots decided to flee France.

Although the Edict of Nantes signed in 1598 by King Henry IV granted toleration to French Protestants, the flow of Huguenots leaving the French kingdom increased during the 17th century. Even more so when Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, creating an exodus of French Protestants who refused to convert to Catholicism.

Among the nations accepting Huguenots on their soil, Ireland became a refuge. An estimated 10,000 Huguenots fled to Ireland following the revocation of 1685, taking great personal risks to evade surveillance by the French army as they slipped out of the country.

Huguenots in Dublin would represent half of those who settled on the island, making their mark on the city. But 300 years on, what is left of the Huguenots in the Irish capital? Let’s dive into Dublin’s forgotten French heritage.

How did the Huguenots influence Dublin?

The Huguenot community, although small, helped shape the Irish city in different ways.

La Touche, From the Battle of the Boyne to Grafton Street

La Touche is a name that pops up here and there in Dublin. The name was given to a bridge built in 1791 over the canal in Portobello. More recently, a building in the IFSC, Dublin’s financial district, was named La Touche House. La Touche, a name so French-sounding that it seems out of place in an Irish city.

David Digues La Touche was an army officer, originally from the Loire region, who fought for William of Orange in 1690 at the Battle of the Boyne. He retired from the army in 1697 and settled in Dublin, where he founded in 1713 the La Touche’s Bank, Ireland’s most successful 18th century bank. Where the money to launch his business originally came from is still unclear, but La Touche became certainly very wealthy.

La Touche then invested in real-estate, buying and developing plots of land around Dublin, a city that was enjoying an economic boom in the 18th century. La Touche was instrumental in developing the St Stephen’s Green – Aungier Street neighbourhood, known today as the Creative Quarter. Streets like Longford Street, Bow Lane, Digges Street, Aungier Street and the famous Grafton Street, were opened by La Touche. Grafton Street, now Dublin’s most sought-after retail district, was then being developed as a fashionable residential area where several Huguenot families resided.

French Walk, Saint Stephen’s Green’s Huguenot Settlement

Salomon Blosset de Loches, Antoine de la Sautié, Charles de Cresserons, Samuel de Thierry de Pechels, Jean Arabin de Barcille : these are a few select names of Huguenots living on the west side of St. Stephen’s Green in the 18th century.

As you walk through Dublin today, it is difficult to imagine that French was once commonly spoken around this now iconic public park in the capital. Due to the significant settlement of French Protestants in the area, by the 1750s, the western side of St. Stephen’s Street was even referred to as French Walk.

On the south side of St. Stephen’s Green, more Huguenot proprietors could be found with names like Daniel de Bouchers de Benâtre, Maximilien Dubois Descourt or Jean de Brasselay. Also a proprietor on the south side, Alexandre de Susy Boan, a Huguenot, was in fact the principal developer of St. Stephen’s Green.

Around St. Stephen’s Green, Dawson Street, Grafton Street, as mentioned earlier, but also Wicklow Street and Exchequer Street off Grafton Street, were favoured by Huguenots who settled in Dublin.

The Forgotten Dutch Billy House

Named after William of Orange, the architectural style flourished especially in late 17th century Dublin with the steady arrival of emigrants from the continent. Imported by French and Dutch Protestants seeking refuge in Ireland, as well as craftsmen from southwest Britain, Dutch Billies gave the streets of Dublin an aestheticism reminiscent of Amsterdam.

Characterised by a gable-ended facade of red bricks, the Dutch Billies dominated the streetscape until the mid 18th century. As the Georgian style became fashionable, most gables were hidden under a new facade or demolished.

Of these elegant houses, few remain today. One example can still be seen at number 66, Capel Street. Dating from the years 1715-1720, the house has retained its curved gable, contrasting with Georgian straight parapets. If you pay attention to the rooflines, you’ll find more Dutch Billies in Aungier Street, Thomas Street, Molesworth Street, South Frederick Street and Temple Bar.

You might also be interested in :

– Guinness’s Goodness To Dublin: Discover The Guinness Legacy

– The 4 Best Distillery Tours in Dublin To Learn About Irish Whiskey

– 6 Easy Day Trips from Dublin by Train

– Ireland Travel Books | The Best Guidebooks to Plan your Irish Adventure

Tracing the Huguenot Presence in Dublin

The Huguenots living in Dublin left limited but still tangible evidence of their presence in the city.

The Lady Chapel, the Huguenot Chapel in St Patrick’s Cathedral

With French Protestants of Calvinist faith arriving in Dublin, the Anglican Church felt the need to control a possible threat if they decided to make common cause with Presbyterian dissenters.

In 1665, the Archbishop of Dublin offered the Lady Chapel within St. Patrick’s Cathedral as a meeting place for conducting services in French under the supervision of the Church of Ireland.

The French parishioners who joined the French Conformist congregation could attend service in French in St. Patrick’s until the early 19th century. One of Dublin’s most illustrious Huguenots, Dr Élie Bouhéreau, first librarian of the Marsh’s Library, was buried here, next to his mother. The French Conformed Church of St. Patrick’s would be known locally as French Patrick’s.

For anyone visiting Dublin for the first time, St. Patrick’s is a must-see. Built in the 13th century, the Lady Chapel is one of its oldest parts. The chapel underwent extensive conservation and refurbishment and reopened in 2013.

Dr. Bouhéreau, a Huguenot First Librarian of the Marsh’s Library

Born in La Rochelle in 1643 in a Protestant family of traders, Élie Bouhéreau, theologist and physician, was barred from practising medicine in his home town because of his faith. Leaving his family in La Rochelle, he moved to Paris then England. He arrived in Dublin in 1697 as secretary of Henri de Ruvigny, Lord Justice of Ireland, with all his family, including his widowed mother, who was approaching 90 years old.

In 1701, Élie Bouhéreau, an eminent scholar, became the first librarian of the Marsh’s Library, founded by Archbishop Narcissus Marsh. The library opened to the public in 1707, becoming Dublin’s very first public library.

No doubt one of the best hidden gems in Dublin, the Marsh’s Library is home to an incredible collection of 16th to 18th century books that belonged to the archbishop. Élie Bouhéreau himself contributed to the collection by donating his private library. It is today one of the oldest libraries in Dublin open to visitors.

In 1701, Bouhéreau was ordained deacon in the Church of Ireland and in 1706, Trinity College granted him the degree of Doctor of Divinity. He remained librarian of the Marsh’s Library until his death in 1719.

In the Heart of the City, Dublin’s 300-year-old Huguenot Cemetery

The French Protestants seeking refuge in Ireland were split in two communities ever since the beginning of their arrivals. The Conformists chose to follow the religious practices of the Church of Ireland, while others remained Calvinists and decided not to conform to the usages of the established Church.

Established in 1693, the Huguenot cemetery in Merrion Row, just across from St. Stephen’s Green, was a burial ground for the French Non-Conformist congregation. Although its access is restricted by a gate and railings, you can still catch a glimpse of the old Huguenot cemetery. Sitting inconspicuously between two buildings, the 300-year-old cemetery appears unaffected by the modern world, protected under the Burial Grounds Act of 1856.

While only 34 tombstones are visible, it is estimated that 600 Huguenots were interred here. The last burials took place in 1901.

What is Left of the Huguenots’ Heritage in Dublin?

The Huguenots of French descent left their mark on the city. Their heritage is still visible in Dublin if you know where to look.

The Streets and Bridges of Dublin Named after Important Huguenot Figures

As mentioned earlier, wealthy David Digues La Touche had a bridge in Portobello named after him. As a successful banker whose family was amongst the original stakeholders of Bank of Ireland, his name was fittingly given to a building in Dublin’s financial district.

Digges Street and Digges Lane (“Digges” being an alternative spelling of “Digues” also found on historical documents) were also named after the real-estate mogul who developed the St. Stephen’s Green – Aungier Street neighbourhood.

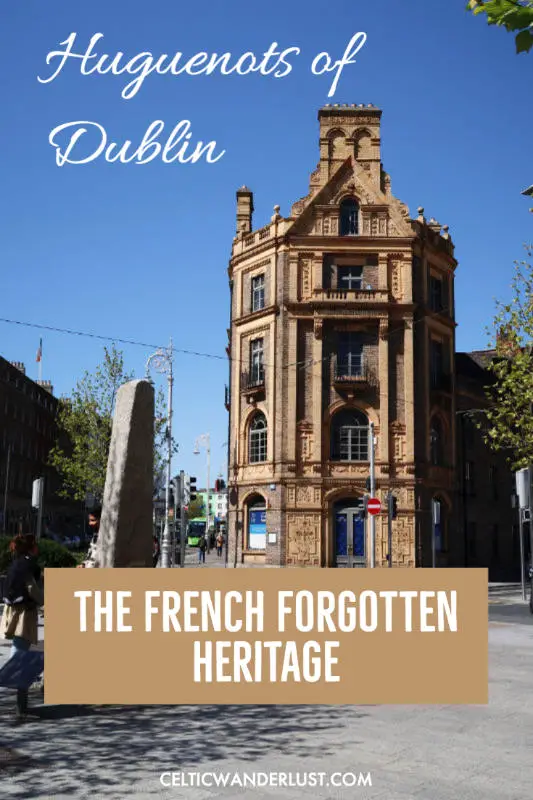

D’Olier Street, a wide thoroughfare nearby Trinity College, is another street in Dublin honouring a Huguenot. The street was named after Jeremiah D’Olier (1745-1817), a goldsmith involved in the establishment of Bank of Ireland. He was also Sheriff of Dublin in 1788. D’Olier Chambers, a remarkable building at the end of the street, didn’t belong to the man, though, as it was built in the late 19th century by a tobacco company.

Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873) is remembered with a park and a road named after the famous Irish writer in the west of Dublin. Born in Dublin into a Huguenot family, Sheridan Le Fanu is best known for his gothic tales and horror fictions. His ancestors may have emigrated from Caen, in Normandy, after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Another famous Irish author of Huguenot descent is celebrated in Dublin with what is probably the most architecturally striking bridge spanning the Liffey: the Samuel Beckett Bridge. One of Samuel Beckett’s relatives is said to be buried in the Huguenot cemetery on Merrion Row under the name of Becqett.

Jacques Tabouré, a Talented French Sculptor in Dublin

After a stint in England, Jacques Tabouré arrived in Dublin in 1682, followed shortly by his brothers Jean and Louis. Known locally as James Taboury, he was hired in 1683 to work on the fitting and embellishment of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham.

His talent as a carver was put to good use in the chapel of the Royal Hospital. He was recorded to have been paid for carving work on the altar, panels and table in the chapel. His brothers, also carvers, might also have been involved in the embellishment under the supervision of James.

The work the brothers accomplished in the chapel constitutes the finest example of woodcarving in baroque style in Ireland. Unfortunately, this admirable work of art cannot be viewed today as the chapel is, sadly, only open for private events.

James Gandon, the Huguenot Architect Who Left His Mark on the City

James Gandon (1742-1823) arrived in Dublin in 1781. Born and bred in London, his grandfather Pierre Gandon was a Huguenot who took refuge in England. James Gandon was tasked to build the Custom House in Dublin, a grand neoclassical building on the banks of the River Liffey. It was officially opened 10 years later, in 1791.

Gandon also left us the Four Courts, Dublin’s main courthouse sitting on Inns Quay. He took over the monumental project following the death of the original architect. Also built in neoclassical style, the Four Courts dominates the streetscape with its magnificent copper dome.

James Gandon also worked on King’s Inn, Dublin’s school of law, and designed O’Connell Bridge, Dublin’s main bridge spanning the River Liffey. The bridge was completed in 1794.

A prolific architect that left his mark on Dublin, he never left Ireland and was buried in Drumcondra cemetery.

With years passing by, the hope of going back to the motherland faded away. In 1787, Louis XVI proposed the Edict of Toleration, granting back French Calvinists their right to practise their religion in the kingdom of France. But for the descendants of the Huguenots refugees in Dublin, it all came a bit too late. The Huguenots had mostly assimilated into the local community, becoming part of Irish history.

Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links. If you click on a link, I earn a little money at no extra cost to you.

RELATED POSTS

Leave a Reply